Western "Experts" and "Intellectuals" Have Become Progressively Incompetent

In an older post, I wrote about how the current generation of political “leaders” in western countries are parasitic PMC-types without any redeeming qualities. What makes this phenomenon especially interesting is that other institutions and areas in the west have seen an identical degradation in their abilities, and over same period of time. This manifests itself in numerous and diverse ways ranging from the inability to build large-scale physical infrastructure or perform scientific research which leads to real advances in quality of life to delusional bureaucrats trying to ban automobiles with internal combustion engines or mandate incredibly stupid policies on topics ranging from farming to hiring people in corporations. While there are those who want to believe that this is all part of a carefully orchestrated masterplan to “destroy the west “, the diverse and ever-expanding list of institutional fails and delusions is much easier to explain if you are willing to accept the possibility that this the result of a systemic trend with considerable support from a significant part of those societies.

To help you better understand what I am talking about, let us initially restrict this discussion to a specific area, namely recruitment into medical school. I am also using this example because the nature of my education and real job allowed me to observe the shifts in this area years before I noticed them elsewhere. So let us start with the observation that first led me to this realization. It began with an interesting pattern about the type of people who were doctors and faculty and medical schools in the late 1990s versus the people they were teaching or supervising. See.. prior to the early- or mid- 1990s (or so it seems), the profile of people who entered medical school was quite different from the types who followed that path from those who did it subsequently. The previous cohort was almost exclusively made up of people who were fairly geeky, not especially socially adept and almost exclusively drawn from the upper-middle class to middle-class. Sure.. there were a few rich kids and some from the working class, but it was mostly academically good and fairly geeky kids from a milquetoast white-collar middle-class background.

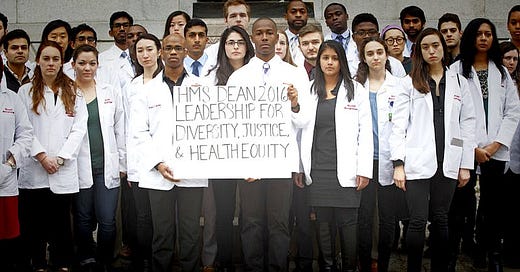

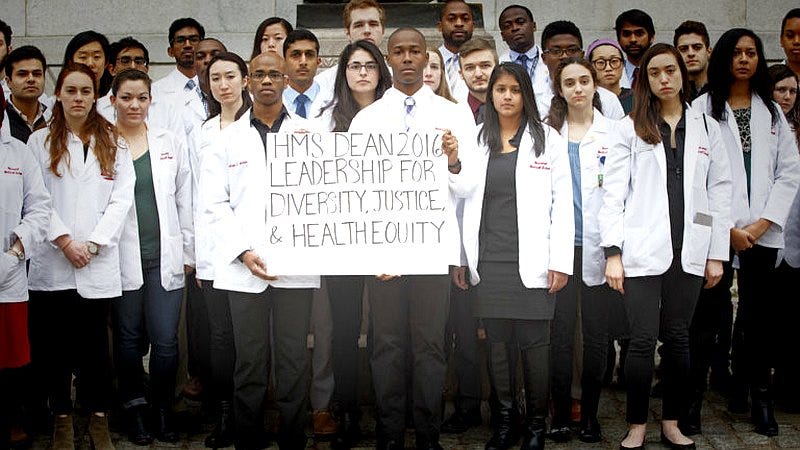

Most of these kids went into med school due to some combination of being interested in medicine, being good at academics and wanting a stable well-compensated career. In other words, they ended up becoming professionals who largely did their job well enough and according to prevailing trends with a minimal of fuss about topics beyond medicine. This, however, started changing in the mid- to late- 1990s when the type of person admitted into medical school started to change. Academic performance and an interest in medicine stopped becoming the major criteria for admissions. Instead, medical programs across North America started paying much more attention to other factors such as the sex of applicant, record of volunteering activities and other self-promoting activities ranging from summer jobs in research to displaying qualities of entrepreneurship- whatever that means. Consequently the unadventurous and geeky but academically good student was progressively replaced by those who got admission due to their sex, volunteering and other instances of self-promotion.

In other words, medical schools increasingly became full of students who were more female, over-socialized, hyper-conformist and without any ideological anchors. This is why, for example, the political leanings of doctors under 40 tend to be quite different from the general population- unlike their predecessors. The new selection process also ended up selecting a cohort with far narcissistic tendencies than used to be the case. So has this had a visible negative influence on the practice of medicine? That depends on what we are talking about.. For example, this unfortunate shift has not yet had a serious negative effect on practice of general medicine because the diagnosis and treatment of upper respiratory/ urinary tract infections or common chronic diseases such as hypertension etc is fairly straightforward and established. Similarly even complex, but routine, surgical procedures such as coronary bypass, joint replacement, surgery or removal of tumors and affected lymph nodes in the abdominal cavity are done using well-established practices and with a massive knowledgebase.

Things get more interesting once you start getting into areas such an oncology or treatment of serious psychiatric conditions- basically stuff that is complicated and not especially common. While many would like to tell you that treatment for all cancers has substantially improved over the past two decades, the reality is far less rosy. While newer drugs such as a few kinase inhibitors, some monoclonal antibodies etc have made large improvements in the outcome of some cancers (CML, melanomas etc) and treatment of previously treatable cancers has also improved, those figures are largely incremental. My point is that the majority of new drugs, protocols, surgical procedures etc to treat cancers have had little to no effect on overall survival rates. The same is true for psychiatry, where the vast increase in number of approved drugs as well as newer theories about serious mental illness have had no beneficial effect on their overall prognosis. With some changes, this holds for many other areas of medicine.

While some may blame this stagnation on “low hanging fruit being picked” or pretend otherwise, it is hard to deny that the past twenty years have seen little improvements in many areas of medicine. This is sharp contrast to the changes between 1940s and 1960s or even between 1970s and 1990s. And it is not as if we have run out of diseases to treat or cure. The prognosis of Alzheimer's and Parkinson Disease hasn’t changed in past two decades, nor have those for common non-hematological cancers. The ability to control and treat Schizophrenia, serious Depression or Hypomania is still stuck in the 1990s. The survival rates for for all of those fancy organ transplantations hasn’t gone up much since the early 2000s. The point I am trying to make is that there has been a serious stagnation in the progress of medicine, medical research and even drug discovery over the past two decades. The only reason things haven’t gotten worse is that we have a large pre-existing knowledgebase of diagnostic techniques, drugs and surgical techniques to take care of many common ailments. As you will see in the next part of this series, the situation is far worse in other areas such as constructing and maintaining infrastructure, keeping supply chains working, managing corporations and other large administrative systems.

What do you think? Comments?